Higher Rates Lock In A Guaranteed Rate of Inflation

And yet, they may help regulate an otherwise "Free for all" financial system

Higher interest rates lock-in a higher rate of inflation. This simple fact requires no empirical evidence, because it is mechanically true. If bonds yield 10%, then your currency MUST inflate 10% relative to bonds. Both bonds and currency are financial assets or debt whose value must be defended their issuer, and if you issue both, then raising interest rates makes the job of fighting inflation in your currency all the more difficult.

As I explained in previous posts, interest rates can viewed as an “intertemporal exchange rate”, which means that if the interest rate is 10%, then $1.10 in one year, is only worth $1 right now in today’s money. You can “buy” $1.10 a year from now, using only $1 of today’s money. If this sounds like inflation, then that is because it IS inflation. If total wealth is increased in the interim, then the CPI level may be stabilized, but the currency still is diluted over that time period, precisely by the interest income offered to maintain that rate.

In the interest of price stability, it may be desireable for nominal interest rates to match otherwise downward changes in the CPI, thus preventing deflation. Nevertheless, a JG can perform virtually the same function, in that deflation with a JG is just an increase in the minimum wage, without the social costs associated with unemployment and financial instability. With a JG, you can avoid a good deal of evictions, foreclosures, debt deflation, unemployment both long and short term, family instability, etc.

A JG is always a better mechanism for fighting deflation than offering interest payments, and that is because a JG purchases labor slack, and favors those willing to work for income, and not passive currency holders. This is especially true if it may be possible that people earned their money through unscrupulous or socially negative means, whether legal or illegal. Interest payments reward everyone who holds currency, while a JG rewards everyone willing to work for public service.

But either way, offering bonds at a given interest rates “locks in” a relative rate of inflation between bonds and currency. If your bonds return 10%, then your currency necessarily inflates 10% more than your bonds. So there is only one sense in which interest can regulate inflation, and that is if you intentionally structure a volatile financial system, that is inclined to periodic instability and disasters.

Some Historical Context on Interest Driven Price Control

Finance and Money have long and complex histories, which we couldn’t possibly cover in this post. Nevertheless, understanding the history of central banking, and how it arose from “lender of last resort” function is important.

Perry Mehrling has authored The New Lombard Street, where he seeks to present what he calls “the money view” to explain financial and economic history. Mehrling is an expert on the history of banking and finance. Mehrling emphasizes this “lender of last resort function” and how it shaped the history of banking up into the modern era. I would recommend researching Perry Mehrling’s comments on the history of finance and banking. From this point on, I will be making my own comments gleaned from a variety of sources, but to understand how “lender of last resort” works, it is hard to find a better source.

While banking was maturing, it was not unusual for banks to issue their own notes that would not trade at par with each other, nor with the state issued currency or “tax credits”. Often a gold standard or other metal standard was used to try to regulate and normalize payments and clearing between banks, although it is important to note that gold and metal standards have been repeatedly adopted and abandoned through history, as gold standards are prone to deflationary instability and tend to promote both fraud and violence, when these metal pegs start to unravel.

It is here, that we see how despite guaranteeing some inflation and/or price instability, interest may be used to attempt to “blow up” an already destabilizing financial free for all in a controlled manner.

Nothing is a better example of this than bitcoin, as high interest rates hit bitcoin very hard. Bitcoin has always been a volatile asset, and while it may appreciate rapidly based on spikes of popularity, it faces considerable problems in that its “Job Guarantee”, the proof of work system, both continually lowers wages according to algorithmic “difficulty” adjustments, and its periodically scheduled “havlings” every 3 years, but perhaps more significantly the “Proof of Work”(ie proof of waste) scheme actively contributes to burning the planet alive, while creating little real financial activity.

So while high interest rates will absolutely lock-in a certain rate of inflation, at least relative to bonds, it can “blow up” other parts of the financial sector much more rapidly. Once investors realize that financial assets must offer some real tangible value, they will quickly abandon infinite duration zero value added assets like bitcoin and similar memes.

We Effect Higher Interest Rates By Paying Out Higher Yields on Treasury Bonds

Much of the discussion on how higher rates actually are implemented can get lost in the shuffle. Since I first started following MMT in 2012, their have even been specific technical changes such as zero reserve requirements, changes to interest on reserves and interest on required reserves.

There may be different ways to view the effect of interest rate adjustments on bond yields. One might claim, that because “investors” are now able to secure higher rates through “money markets”, that they will demand higher rates on treasury securities.

Nevertheless, seeing as we effect changes in the federal funds rate, by mechanisms such as open market operations, where the federal reserve buys and sells the national debt, it is much more clear to simply say, we raise the interest rate by increasing yields on treasury securities. Whether we call this “national debt” or “national savings accounts” is a matter of convention, and while calling it savings accounts is much more descriptively accurate, the phrase “national debt” is the term that is intentionally chosen by neoliberals. Neoliberalism is a doctrine of the supremacy of private wealth to public wealth, and more specifically that wealth itself must be protected, regardless of who holds it or how it is distributed. While a balanced view would consider both private and public wealth to be important, neoliberalism tries to shift the narrative to exclusively be about private wealth. In this case, maintaining unequal and socially destructive relationships is not a bad thing, so long as it supports higher asset valuations. This pattern is a common theme behind, high housing costs, unemployment which hits middle and lower classes much worse, and yes, the payment of interest on public money.

Paying interest on public money makes no sense, as public money should be earned from public service. Seeing as the public does not have to seek capital, but rather simply taxes to reserve economic space and create unemployment, interest on public money makes no sense.

Interest on private credit relationships has benefits, specifically it is the “wages of bankers”, nevertheless, there is no special reason for credit markets to have a universal equilibrium. We would not expect the market on carrots and cheese to be exactly the same, so there is no reason to expect an equilibrium between classes of “credit creation”. This is especially apparent once it become clear the credit and money are both created from nothing in an informational sense, and backed not by previous capital accumulation, but instead backed by the very project they are created to finance.

A mortgage is backed by the house which that credit is used to buy. A business loan is backed by the business built with that credit creation. Both credit and money creation do not rely on existing financial capital, but rather external, unaccounted wealth, which is then “brought into” or “incorporated” into the financial system.

So capital does not need to be accumulated, but rather social trust and credibility, which then organizes the efforts that it “sponsors”. The money, stock, currency, bonds, or deposits you are paid, are backed by the active efforts of the project being financed, not some accumulated “money” or previously incorporated financial assets. Credit and money are always backed by the new wealth they create, not just the existing wealth you have to recruit to get started.

While that may sound long and complex, interest free public money has a compelling empirical foundation, and that is the correlation between bond yields and the fed funds effective rate. So the only question is, “who do we really want to pay? hodlers or workers”

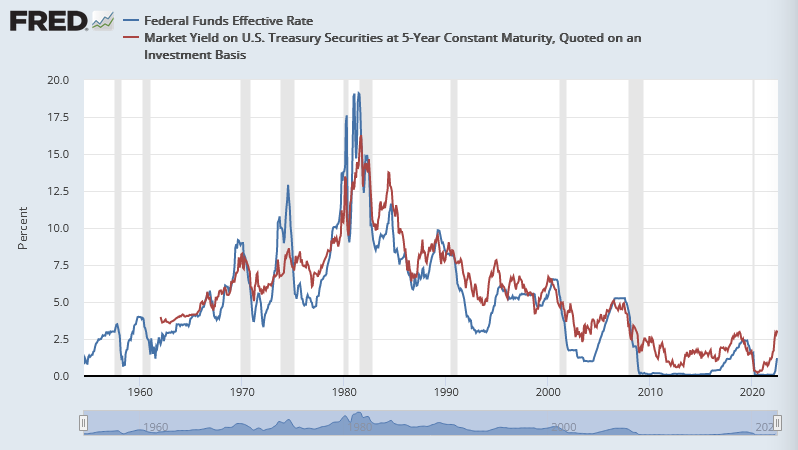

As you can see easily in this graph, what we pay out on the national “debt”, is just a matter of the interest rate the federal reserve sets.

Edit: since originally writing

this piece, I have changed the word "guarantee" to "lock-in", as I

believe that more accurately represents how interest rates work as

either a transfer or redenomination.

Well said in general!

ReplyDelete